Note: This post is highly related to the research performed by Alex Ionescu. He is going to present the results of his work on the RECON2010 conference, during his Debugger-based Target-to-Host Cross-System Attacks speech. As it turns out, Alex and I have been working on the same subject concurrently – while I have only managed to perform cursory analysis of the mechanism, Alex has carried out a thorough analysis and possibly developed a PoC for a real vulnerability ;) Besides this, I would like to share some of my ideas and conclusions which I came up with, during a short period of the recent weeks ;)

Introduction

Nowadays, all of the classic Virtual Machine products (Microsoft Virtual PC, VMWare Workstation, Oracle VirtualBox) are widely-spread and commonly used for a variety of purposes. That’s because of the fact that they provide a reliable and convenient environment for multiple, virtual operating systems, which can be employed by Software Developers, Web Developers, Reverse-Engineers or even people not related to the IT industry, at all. As for one of the most significant advantages of using VMs, is that they are supposed to run in complete separation from the host system. Numerous security professionals take advantage of this assumption by setting up malware-dedicated guest systems, where the samples can be observed and safely debugged at run-time.

Nowadays, all of the classic Virtual Machine products (Microsoft Virtual PC, VMWare Workstation, Oracle VirtualBox) are widely-spread and commonly used for a variety of purposes. That’s because of the fact that they provide a reliable and convenient environment for multiple, virtual operating systems, which can be employed by Software Developers, Web Developers, Reverse-Engineers or even people not related to the IT industry, at all. As for one of the most significant advantages of using VMs, is that they are supposed to run in complete separation from the host system. Numerous security professionals take advantage of this assumption by setting up malware-dedicated guest systems, where the samples can be observed and safely debugged at run-time.

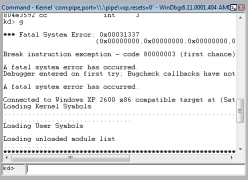

As it turns out, however, it might be possible to escape from a live guest OS right into the Host, under certain circumstances. WinDbg – the most commonly used debugger (working in both local and remote mode) developed by Microsoft, is confirmed to be vulnerable to multiple flaws, and/or makes use of vulnerable libraries. These security flaws could potentially lead to information disclosure (in case WinDbg leaks memory chunks to the guest), or even code execution in the context of the remote debugger process (running on the host OS). What should be noted, is that the attack vector is debugger-specific and can only be triggered in very specific conditions (hence being useless without a debugger being attached, in the first place).

Background

These days, the debugging software seems to be the integral part of any development environment – whenever new software of any kind is being developed, various kinds of errors tend to appear on both logical and implementation levels of the new code. These issues must often have to be dealt with using run-time analysis, which includes stepping through the code, examining and altering parts of the processor context (register, flags) and program state (in-memory variables etc). There’s not much of a problem when it comes to user-mode, as Windows kernel provides debugger support (both in kernel- and user-mode parts of the system), and a decent number of ring-3 debuggers is freely available. Things are more interesting in the context of kernel-mode, which also has to be analyzed in many different situations (malware analysts, driver developers, bug-hunters and others). In order to begin the Kernel Debugging process, two (logical) live machines are required – the target (guest) and host computers, most likely connected via the serial port (though USB and IEEE1394 are also supported on the latest Windows versions). When the physical connection is correctly set-up, the Kernel Debugger (also referred to as “KD” later in this post) built-in part of the target system core begins exchanging data with WinDbg (or potentially any software supporting the undocumented communication protocol).

These days, the debugging software seems to be the integral part of any development environment – whenever new software of any kind is being developed, various kinds of errors tend to appear on both logical and implementation levels of the new code. These issues must often have to be dealt with using run-time analysis, which includes stepping through the code, examining and altering parts of the processor context (register, flags) and program state (in-memory variables etc). There’s not much of a problem when it comes to user-mode, as Windows kernel provides debugger support (both in kernel- and user-mode parts of the system), and a decent number of ring-3 debuggers is freely available. Things are more interesting in the context of kernel-mode, which also has to be analyzed in many different situations (malware analysts, driver developers, bug-hunters and others). In order to begin the Kernel Debugging process, two (logical) live machines are required – the target (guest) and host computers, most likely connected via the serial port (though USB and IEEE1394 are also supported on the latest Windows versions). When the physical connection is correctly set-up, the Kernel Debugger (also referred to as “KD” later in this post) built-in part of the target system core begins exchanging data with WinDbg (or potentially any software supporting the undocumented communication protocol).

When the guest system is running, the remote debugger resides in the idle state, waiting for one of the following events to happen:

- A certain event occurs inside the guest, which requires the debugger to be informed about it,

- A special (native) request is received from the guest (such as a DbgPrint request, resulting in printing a user-defined message on the debugger console),

- The user decides to intercept the OS execution in the middle of its work (e.g. to set a breakpoint),

The first situation happens whenever an exception is raised, a breakpoint is reached or the system crashes with a Blue Screen of Death. The second and third will be described in more details later.

In case any of the above conditions is met, the control is passed to the remote debugger, consequently leading to the target OS getting temporarily frozen. When WinDbg’s is in control, the user is able to perform actions such as managing (setting, removing, enabling) the breakpoints, modifying memory, examining and altering the processor context and so on. During all the time, when WinDbg is instructed to execute these operations, the guest execution is suspended – the only way for it to get back to work requires the debugger to issue a special Resume packet. What should be also noted is that most of the debugging features can only be taken advantage of when the debugger resides in the stand-by mode. An exception of this rule is the break-in action (otherwise known as CTRL-C), which can be used any time, in order to break into the debugger.

Due to the fact that a majority of kernel debugging is performed using Virtual Machines, and because most malware analysts use these techniques in their daily work, escaping from the virtual environment by any means (i.e. execute code on the host system) can pose a real threat these days. In this post, I would like to present some of the possible attack scenarios and vectors, which could be potentially used to perform in-the-wild attacks in the future.

First attack vector – the KDCOM protocol

The basics

The overall idea behind the reserach is “wherever data exchange takes place, a security flaw is likely to appear”. In this case, the data in consideration is being passed between WinDbg.exe and the Virtual Machine process (whichever one we choose – it doesn’t really matter at this point). Although, before lurking into some advanced communication internals, let’s get a quick insight into the basics.

The overall idea behind the reserach is “wherever data exchange takes place, a security flaw is likely to appear”. In this case, the data in consideration is being passed between WinDbg.exe and the Virtual Machine process (whichever one we choose – it doesn’t really matter at this point). Although, before lurking into some advanced communication internals, let’s get a quick insight into the basics.

First of all, before trying to perform kernel debugging, one must make sure that the physical (in case of two real computers), or software – e.g. named pipes (in case of a VM) connection can be successfully established. Furthermore, the guest must be also booted up with adequate boot-settings – i.e. the /DEBUG flag set in the boot.ini configuration file for Windows XP and earlier, or using the bcedit.exe utility on Windows Vista and later.

The entire debugging session can be carried out thanks to the packet-based protocol, used by the host and guest to understand each other. As WinDbg is the only application capable of debugging a remote Windows OS, plus Microsoft doesn’t intend the things to change, no official documentation has been published by the vendor, so far. On the other hand, some people have put effort in order to understand the proto and create a thorough reference, uncovering most of the technical details. Two, very appreciable articles can be found here: Kernel and remote debuggers and here: KD extension DLLs & KDCOM protocol, covering the precise way of how the target’s kernel deals with the remote debugger. As can be seen, the protocol isn’t very complex in general, though supports a great number of cross-system operation codes. Let’s find out how the packet structure looks like.

The entire packet consists of two, main parts – the header, let’s call it KD_PACKET_HEADER and the packet body, which is specific to the operation type defined in the header. Let’s take a look at the header layout, in the form of a C structure:

typedef struct _KD_PACKET_HEADER

{

DWORD Signature;

WORD PacketType;

WORD DataSize;

DWORD PacketID;

DWORD Checksum;

BYTE PacketBody[1];

} KD_PACKET_HEADER, *PKD_PACKET_HEADER;

Let’s focus on each and every of the structure fields:

- Signature Can be either 0x30303030 (‘0000’) or 0x69696969 (‘iiii’). The first value represents Data Packets, while the latter one is used for marking Control Packets,

- PacketType Defines the type of the request,

- ByteCount Defines the length of the PacketBody array – containing necessary information – assigned to the request type,

- PacketID Used to detect synchronization issues,

- Checksum A straight-forward sum of all the bytes inside PacketBody (specifically zero, if ByteCount = 0),

- PacketBody Type-specific data.

The PacketType field must be one of the following enum values:

enum KD_PACKET_TYPE

{

PACKET_TYPE_UNUSED = 0,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_STATE_CHANGE32 = 1,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_STATE_MANIPULATE = 2,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_DEBUG_IO = 3,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_ACKNOWLEDGE = 4,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_RESEND = 5,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_RESET = 6,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_STATE_CHANGE64 = 7,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_POLL_BREAKIN = 8,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_TRACE_IO = 9,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_CONTROL_REQUEST = 10,

PACKET_TYPE_KD_FILE_IO = 11

};

A quick explanation for some of the above types follows:

- Acknowledgement packets – used to confirm that a specific packet has been successfully received – sent by both Windbg and the target,

- Resend packets – used, when Windbg or the target considers a specific packet invalid (e.g. the Checksum value is incorrect, given the packet data),

- Resync packets – used, when the synchronization between two machines fails.

For a more detailed (or better visualized) information on how a successful packet exchange is achieved, take a look at the aforementioned KD extension DLLs & KDCOM protocol text, section KDCOM protocol.

Furthermore, if we take a closer look at the structure definitions for each of the above types, we can easily observe a certain characteristic, which is true for most of the packets:

typedef struct _DBGKD_DEBUG_IO

{

ULONG ApiNumber;

USHORT ProcessorLevel;

USHORT Processor;

union

{

DBGKD_PRINT_STRING PrintString;

DBGKD_GET_STRING GetString;

} u;

} DBGKD_DEBUG_IO, *PDBGKD_DEBUG_IO;

typedef struct _DBGKD_CONTROL_REQUEST

{

ULONG ApiNumber;

union

{

DBGKD_REQUEST_BREAKPOINT RequestBreakpoint;

DBGKD_RELEASE_BREAKPOINT ReleaseBreakpoint;

} u;

} DBGKD_CONTROL_REQUEST, *PDBGKD_CONTROL_REQUEST;

Noticeably, a majority of the type-specific structures begin with an ApiNumber field, containing the sub-type of the packet. For example, if the target encounters a PACKET_TYPE_KD_STATE_CHANGE type, then the correct value of the ApiNumber field must be one of the following:

enum KD_STATE_CHANGE_API_NUMBER

{

DbgKdExceptionStateChange = 0x00003030L,

DbgKdLoadSymbolsStateChange = 0x00003031L,

DbgKdCommandStringStateChange = 0x00003032L

};

PACKET_TYPE_KD_DEBUG_IO packet type, together with the supported APIs can be another good example:

enum KD_DEBUG_IO_API_NUMBER

{

DbgKdPrintStringApi = 0x00003230L,

DbgKdGetStringApi = 0x00003231L

};

Please note that all of the constants and structure definitions can be found in the windbgkd.h file included in Windows 2000 DDK, or the ReactOS project files.

In general, the entire cross-system communication is carried out using the packet format presented above. Later in this post, I will show you how the data exchange looks in practise.

Previous research & related stuff

As mentioned before, several people have decided to analyze and describe the strictly technical details related to Kernel Debugger communication. Apart from great articles, a few KD-related projects have also been started, some of which are successfully developed until today. If you’re interested in this subject, you should check out the following links:

- SYSPROGS VirtualKD – a project officially named Windows Kernel Debugger booster for Virtual Machines, which is supposed to speed up the Windows kernel debugging process, for both VMWare and VirtualBox software. The effect can be achieved by replacing the standard virtual COM port (allowing 115200 bps transfer) with a custom mechanism, reaching up to 450KB/s (VirtualBox) or 150KB/s (VMWare) transfer rate. Thanks to the author, both the binaries and source code are available, making it possible to build the executable images on one’s own, or even learn how the program works under-the-hood. Download: http://sourceforge.net/projects/virtualkd/

- SecureWorks Wind Pill – a perl tool, which aims at automating the tasks involved in debugging the Windows kernel. Using this script, it becomes possible to carry out a kernel debugging session on custom host platforms. Besides, the utility makes it much easier to perform certain tasks (able to be automated) on the target system, which would be harder to achieve using the standard Windbg scripting abilities. Black Hat USA 2007 presentation: https://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-usa-07/Stewart/Presentation/bh-usa-07-stewart.pdf, Source Code: http://www.secureworks.com/research/tools/windpl.zip

Pipe Proxy – traffic monitor

In order to observe, how the communication between the two systems is really achieved, I have written a straight-forward tool called Windbg-PipeProxy, which works just as the name suggests – becomes a named-pipe proxy between the guest and host, and redirects every single packet sent by either of the systems. Apart from forwarding the traffic, a more or less reader-friendly log messages are emitted, giving some insight on what type of information is really passed to and from the kernel debugger. In the long haul, this can provide possible ideas of how the debugger can be actually attacked by the host system. Examples:

- Windbg tries to connect to the booting machine by sending the PACKET_TYPE_KD_RESET packet (type 6):

---==[ WinDBG ---> VirtualPC ]==--- [14:38:12] Leader: 0x69696969 S --> C Type: 0000000006 S --> C Bytes: 0 S --> C Checksum: 0x00000000

- Windbg sends a BREAKIN packet (single 0x62 byte):

---==[ WinDBG ---> VirtualPC ]==--- [14:38:12] Leader: 0x00000062 S --> C Type: 0000000000 S --> C Bytes: 0 S --> C Checksum: 0x00000000

- Windbg send a GetVersion request to the Virtual Machine…

---==[ WinDBG ---> VirtualPC ]==--- [14:38:15] Leader: 0x30303030 S --> C Type: 0000000002 S --> C Bytes: 56 S --> C Checksum: 0x00000610 00000000: 46 31 00 00 00 00 00 00 03 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 F1.............. 00000010: b8 f8 c7 02 01 00 00 00 30 d1 52 69 00 00 00 00 ........0.Ri.... 00000020: aa 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 53 61 00 00 ............Sa.. 00000030: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ................ 0x00003146 = DbgKdGetVersionApi

- … and the guest system responses with a correctly filled structure:

---==[ VirtualPC ---> WinDBG ]==--- [14:38:15] Leader: 0x30303030 C --> S Type: 0000000002 C --> S Bytes: 56 C --> S Checksum: 0x0000149e 00000000: 46 31 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 F1.............. 00000010: 0f 00 bc 1b 06 00 03 00 4c 01 0c 03 2f 00 00 00 ........L.../... 00000020: 00 a0 83 82 ff ff ff ff 70 95 97 82 ff ff ff ff ........p....... 00000030: ec cf b9 82 ff ff ff ff ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ................ 0x00003146 = DbgKdGetVersionApi 0xffffffff`8283a000 = NT Kernel ImageBase 0xffffffff`82979570 = PsLoadedModuleList 0xffffffff`82b9cfec = DebuggerDataList

- A user-mode application uses ntdll.DbgPrintEx to send out a simple text message to the debugger console.

---==[ VirtualPC ---> WinDBG ]==--- [15:29:16] Leader: 0x30303030 C --> S Type: 0000000003 C --> S Bytes: 29 C --> S Checksum: 0x000007f2 00000000: 30 32 00 00 10 00 00 00 0d 00 00 00 f9 fc b5 82 02.............. 00000010: 48 65 6c 6c 6f 20 57 6f 72 6c 64 21 0a ?? ?? ?? Hello World!....0x00003230 = DbgKdPrintStringApi 0x0000000d = Output string length 'Hello world!\n' = Output string contents

- A user-mode application uses ntdll.DbgPrompt to send a request for input data from the KD, providing prompt text…

---==[ WinDBG ---> VirtualPC ]==--- [15:20:21] Leader: 0x30303030 C --> S Type: 0000000003 C --> S Bytes: 31 C --> S Checksum: 0x0000061c 00000000: 31 32 00 00 10 00 00 00 0f 00 00 00 20 00 00 00 12.......... ... 00000010: 48 65 6c 6c 6f 20 64 65 62 75 67 67 65 72 21 ?? Hello debugger!. 0x00003231 = DbgKdGetStringApi 0x0000000f = Prompt string length 0x00000020 = Output buffer size 'Hello debugger!' = Prompt string contents

- … and Windbg responses with an input string:

---==[ WinDBG ---> VirtualPC ]==--- [15:20:26] Leader: 0x30303030 C --> S Type: 0000000003 C --> S Bytes: 30 C --> S Checksum: 0x00000544 00000000: 31 32 00 00 10 00 00 00 0f 00 00 00 0e 00 00 00 12.............. 00000010: 48 65 6c 6c 6f 20 63 6c 69 65 6e 74 21 00 ?? ?? Hello client!... 0x00003231 = DbgKdGetStringApi0x00000010 = unchanged 0x0000000f = unchanged 0x0000000e = the actual size of the output string (must be less or equal to the buffer size defined in the previous packet) 'Hello client!' = The text message typed by the KD use

- The debugger requests 0x18 bytes to be read from the specified virtual memory address…

---==[ WinDBG ---> VirtualPC ]==--- [15:14:15] Leader: 0x30303030 C --> S Type: 0000000002 C --> S Bytes: 56 C --> S Checksum: 0x0000078b 00000000: 30 31 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01.............. 00000010: e8 3b 95 82 ff ff ff ff 18 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 .;.............. 00000020: 42 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 0f 00 00 B............... 00000030: 00 00 0f 77 01 00 00 00 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ...w............ 0x00003130 = DbgKdReadVirtualMemoryApi 0xffffffff`82953be8 = Memory address to read 0x00000018 = Byte count

- … And the kernel supplies the data in consideration.

---==[ VirtualPC ---> WinDBG ]==--- [15:14:15] Leader: 0x30303030 C --> S Type: 0000000002 C --> S Bytes: 80 C --> S Checksum: 0x00000e08 00000000: 30 31 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01.............. 00000010: e8 3b 95 82 ff ff ff ff 18 00 00 00 18 00 00 00 .;.............. 00000020: 42 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 0f 00 00 B............... 00000030: 00 00 0f 77 01 00 00 00 ec 5f b9 82 ec 5f b9 82 ...w....._..._.. 00000040: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 4b 44 42 47 40 03 00 00 ........KDBG@... 0x00003130 = DbgKdReadVirtualMemoryApi 0xffffffff`82953be8 = Memory address to read (unchanged) 0x00000018 = Byte count (unchanged) 0x00000018 = Number of bytes read ###Data### = Requested memory contents, appended to the primary packet

- Apart from the normal, functional packets, the ACK packets are continuously sent after the KD / kernel successfully receives a message from the other side:

---==[ WinDBG ---> VirtualPC ]==--- [15:14:15] Leader: 0x69696969 S --> C Type: 0000000004 S --> C Bytes: 0 S --> C Checksum: 0x00000000 ---==[ VirtualPC ---> WinDBG ]==--- [15:14:15] Leader: 0x69696969 C --> S Type: 0000000004 C --> S Bytes: 0 C --> S Checksum: 0x00000000

One should also note that the maximum size of the overall packet is a constant value 0f 4000 (0xFA0), and cannot be extended by any means:

#define PACKET_MAX_SIZE 4000

This, in turn, indicates that when the KD requests for more than one typical memory page (4096 bytes), the replies are sent in a chunked form, where each packet contains a separate memory area and fits in the packet size limitation. Furthermore, it is not possible to correctly send an debug message longer than ~4000 bytes, as well as send an input string to the kernel, either.

The above listings should give you some insight at how the communication is performed – please keep in mind that the number of supported APIs is more than 50, while almost every single one has its own, unique structure – definitely worth taking a closer look at. If you would like to receive more packet samples, complete dumps of a debugging session or even the source code, feel free to contact me.

Pipe Proxy – fuzzing the packets

Already being able to monitor and observe the flowing packets, the next step on the way to find some real vulnerability required modifying the packets. More precisely, the first idea was to pick random bytes and alter them before passing to to the adequate pipe – a technique otherwise known as fuzzing. Due to the fact that the first PipeProxy version was unable to recognize the packet structure, only a fully raw-data fuzzing was possible. As it later turned out, the only thing I could achieve by doing this, was hanging the entire debugging session after a couple seconds.

The reason of such behavior was pretty simple – both sides of the communication were validating the packet body against the Checksum field – if the verification failed, the message was requested to be re-sent. Apparently, more intelligent fuzzer was required to deal with this issue. And so, packet buffering was implemented, which guaranteed that each packet is entirely received before sending it to the other party. By doing so, random bytes could be chosen out of the packet body and changed – next then, the Checksum was re-calculated and sent to the dest~ pipe. After this fix, the fuzzer seemed to work well, as the debugger really started to behave unexpectedly.

Results

Unfortunately, the bad news is that during a couple fuzzing sessions, Windbg seemed to work steadily when parsing malformed protocol structures. The interesting thing is that strange things began happening when the packet’s body (e.g. the memory contents read from the machine) was fuzzed together with the protocol structures. More precisely, exceptions started to be raised inside external DLL modules utilized by Windbg.exe. This phenomenom gave me the idea that the KD could possibly have problems handling the Virtual Machine’s internal state, as well. More information regarding some real security flaws can be found in the “second attack vector” section :-)

Please note, that the fact that no serious issues were found (yes, there were some minor cases) in relation to the packet format, doesn’t necessarily mean that Windbg is vulnerability-free in this context. Don’t hesitate to make your own experiments in this area :-)

Source Code

On a second thought, I decided not to make the Windbg-PipeProxy available for the public audience for now. Chances are that you can get it after contacting me on a private channel, but no guarantee regarding this. I’ve got plans to release the tool soon though, so you can patiently wait or create one on your own :-)

Second attack vector – executable image symbols’ support

The basics

As a very advanced debugger, Windbg can obviously make use of symbols of any kind (export names, additional .pdb symbol files – both locally and remotely) if the user desires to do so. The symbol packages for each Windows version can be downloaded here, together with other debugging tools. If the Kernel Debugger can assign virtual addresses to the names exported from both user- and kernel-mode modules, it must somehow calculate the addresses, based on the current VM state (i.e. memory layout). The question is – does Windbg parses the PE and possibly PE32+ format manually? The answer is – yes and no.

As it turns out, Microsoft has developed a couple of libraries, aiming to help the developers in writing both user- and kernel- mode debugger applications. These libraries make it possible to focus on the real debugger functionality and usability, rather than implementing all the core operations from stratch; as they are really convenient, most of the modern debugging software makes use of these libs. These DLLs are:

- The Debugger Engine (DbgEng.dll)

As MSDN states:The debugger engine (DbgEng.dll), typically referred to as the engine, provides an interface for examining and manipulating debugging targets in user mode and kernel mode on Microsoft Windows. The debugger engine can acquire targets, set breakpoints, monitor events, query symbols, read and write to memory, and control threads and processes in a target. You can use the debugger engine to write both debugger extension libraries and stand-alone applications. Such applications are referred to as debugger engine applications. A debugger engine application that uses the full functionality of the debugger engine is called a debugger. For example, WinDbg, CDB, NTSD, and KD are debuggers; the debugger engine provides the core of their functionality.

- The Debug Help Library (DbgHelp.dll) – a small helper library, providing support to all symbol-related activities, as well as minidump files’ management. This module is actually responsible for parsing all the internal PE/PE32+ structures of a specific image, on the debugger’s demand.

Noticeably, Windbg takes advantage of both of these libraries. All in all, even if the debugger itself doesn’t have problems dealing with malformed packet structure, both external DLLs are also directly operating on the information provided by the target kernel. Compromising the security of one of these modules would be as good as owning Windbg.exe itself – either way, the code’s executing with the same privileges.

I have personally focused on the latter one, which has already been proven to contain critical security flaws. Let’s take a look if there’s anything left for us :-)

Previous research & related stuff

One or two buffer overflow vulnerabilities were found and exploited during recent years. Some references:

- OllyDBG v1.10 and ImpREC v1.7f export name buffer overflow vulnerability – tuts4you forums discussion

- Old dbghelp and an old exploit… – a brief analysis of a stack-based BO by ReWolf

Even thought that’s not much, these sources can reveal the actual code quality provided by DbgHelp.dll. For more details on how it really looks like, take a look at the next section :-)

PE Image Fuzzing (environment + process)

In my opinion, running a fuzzer for a couple of nights is one of the most efficient ways of finding some anchor points, which can be further analyzed in order to work out a code-exec exploit; this case is no different. Before I start listing bugs found in the aforementioned DLL, one thing must be noted: Because of the fact that the target kernel has complete control over the data being sent to the debugger, one can simply fuzz the DbgHelp.dll library without Windbg taking part in this process – every malformed .exe loaded in the context of a local fuzzer can also be loaded by Windbg.exe, when the guest decides to.

Okie, let’s take a look at a brief explanation of a some of the DbgHelp bugs:

-

Type: Out-of-bounds memory reference (READ) Instruction: rep movsd, [ESI]=??? Call Stack: msvcrt!memcpy dbghelp!ReadImageData dbghelp!ReadHeader dbghelp!imgReadFromDisk dbghelp!modload dbghelp!LoadModule dbghelp!SymLoadModuleEx (exported)Description: this exception can be raised thanks to lack of sanity checks in numerous places, e.g. when (IMAGE_FILE_HEADER.NumberOfSections * sizeof(IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER)) is greater than the executable image size

-

Type: Invalid Memory Reference (READ) Instruction: movzx eax, word ptr [edx+ecx*2], EDX=controlled Call Stack: dbghelp!LoadExportSymbols dbghelp!idd2me dbghelp!modload dbghelp!LoadModule dbghelp!SymLoadModuleEx (exported)Description: the instruction is a part of a loop, which parses respective Export Table entries. The above instruction loads the ordinal of the current routine into AX – any address can be specified as the source operand, here.

-

Type: Out-of-bounds memory reference (READ) Instruction: mov edx, [ecx+eax*4], LO(EAX)=controlled Call Stack: dbghelp!LoadExportSymbols dbghelp!idd2me dbghelp!modload dbghelp!LoadModule dbghelp!SymLoadModuleEx (exported)Description: the code tries to retrieve the address/name of the currently-processed function, using the export ordinal as an array index. Because of the fact that the buffer allocation size is determined by max(NumberOfFunctions,NumberOfNames), and the ordinals are not compared against the buffer size, one can reference heap data after the buffer.

-

Type: Invalid Memory Reference (READ) Instruction: movzx eax, byte ptr [edx+10h], EDX=controlled Call Stack: dbghelp!LoadCoffSymbols dbghelp!idd2me dbghelp!modload dbghelp!LoadModule dbghelp!SymLoadModuleExDescription: just another controlled memory reference while parsing the coff symbols.

- A bunch of similar invalid memory references controlled by the VM. Although these bugs doesn’t directly lead to any thread, a few information-disclosure attacks are confirmed to be possible (i.e. revealing Windbg.exe process memory to the guest).

-

Type: Out-of-bounds memory reference (WRITE) Instruction: mov word ptr [eax+edx*2], cx LO(EDX)=controlled CX=0x0001 Call Stack: dbghelp!LoadExportSymbols dbghelp!idd2me dbghelp!modload dbghelp!LoadModule dbghelp!SymLoadModuleEx

Description: The LoadExportSymbols functions allocates a special array on the heaps, let’s call it IsOrdinalPresent. Its size (in items) is set to max(NumberOfFunctions,NumberOfNames), while the size of a single item is 16-bits. During the export directory parsing, the routine marks the ordinals as present by putting a TRUE value into the corresponding array index. Noticeably, the actual value of the ordinal is not validated and can exceed the size of the buffer. This flaw makes it possible for us to overwrite the memory following our buffer with (WORD)1. Considering today’s Windows heap protections, it might be particurarly hard to transform this bug into a reliable code-execution; but who knows, it still might be possible (i.e. by targetting the heap allocation contents instead of headers).

-

Type: 32-bit Integer Overflow Instructions: mov edx, [ebp-864], EDX=controlled shl edx, 1 push edx call _pMemAlloc Call Stack: dbghelp!LoadExportSymbols dbghelp!idd2me dbghelp!modload dbghelp!LoadModule dbghelp!SymLoadModuleExDescription: Because of the fact that the ordinals aren’t validated either way when being used as a WRITE array index, the bug doesn’t change anything. If, however, an appropriate check would be added in order to accept ords integer overflow would still make it possible to perform out-of-bounds writing e.g. by setting the NumberOfFunctions field to 0x80000001 – then:

(uint32_t)(NumberOfFunctions * 2) = 2

As can be seen, DbgHelp.dll contains numerous places where virtually any value could be used as the read instruction operand. Unfortunately for us, the library makes use of multiple exception handlers, which do their best not to have the process crashed; most of the Access Violation exceptions are correctly dealt with. However, it is still possible to cause serious damage on the Windbg.exe heap (using out-of-bounds write), which would eventually lead to Denial of Service conditions. Code execution has not been confirmed due to very hard exploitation conditions of the known flaws – I strongly believe that it is possible, though.

Conclusions

As shown in this post entry, using a remote debugger might not be as safe as one might expect. Wherever information is exchanged, a vulnerability is likely to appear – this phrase perfectly fits to the issues described here.

Please keep in mind that the results presented here are not the results of a really thorough research – Alex appeared to be faster than me :-) This means that I could have missed some obvious vectors which should be double-checked – in this case, please just let me know. Additionally, you are free to carry out your own analysis of the Kernel Debugger security – however, if you’re going to make use of some ideas / conclusions included in this post, I’d be really glad to be let known :) Thanks!

Good stuff! :-)

Awesome write-up j00ru :)

Mind Blowing – Keep it coming!

Cool, glad you guys like it ;>